Three internationally renowned academics visited HKUST earlier this year, and talked about the future of employment. Their discussion reflected on everything from potential new relationships between man and machine to the positive role business schools can play in shaping tomorrow’s world.

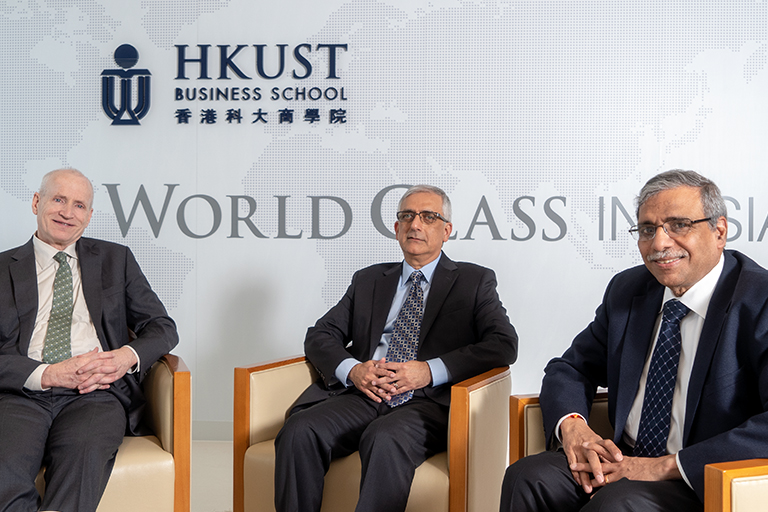

(From left) Professor Edward A. Snyder – Dean, School of Management, Yale University; Professor Arun Rai – Regents Professor, Robinson College of Business, Georgia State University; and Professor Dipak Jain – European President of CEIBS

Speaking on this topic were: Edward SNYDER, the Indra K Nooyi Dean and William S Beinecke Professor of Economics and Management at the Yale School of Management; Dipak Chand JAIN, European President and Professor of Marketing at the China Europe International Business School (CEIBS); and Arun RAI, Regents’ Professor at the Robinson College of Business at Georgia State University.

Replaced or supported

Professor Rai began by breaking down the likely effects on employment of digital technology into three categories.

“There are certain areas where we’re going to see AI essentially substitute for human labor,” he says. Industries, both in the manufacturing and services sectors, whose inputs and outputs are clearly defined and whose processes are repetitive, would fall into this grouping.

In the second category, AI will augment human capabilities by playing an advisory role. One of the leading causes of diagnostic error in medicine is premature closure, when a physician makes a quick diagnosis of a patient’s condition, Professor Rai explains. “In this case, the AI system will essentially challenge the physician and present them with additional options.”

Finally, there’s the collaborative execution of much more complicated distributed processes. “A great example of this is where you have robotic surgery, with the physician and robot working together even though the physician is not on site.” The robot performs the surgery under the remote guidance of the physician.

The overall challenge, though, is to find the most effective ways in which humans and machines can collaborate, Professor Rai notes. “When it comes to creativity, we can understand contextual nuances that machines may not be able to observe as well. But when it comes to handling data on a large scale, there’s no contest.”

He believes, even though advances in technology will spawn new industries offering new employment opportunities, the transition to the future economy will not be friction free.

Disrupting society

The severity of this friction is something that concerns Professor Snyder – even though he does have confidence that developments in digital technology will, ultimately, have a positive impact on society. He believes these developments are likely to transform almost every area of economic activity, risking initial social dislocation on a scale that goes well beyond even what happened during the Industrial Revolution.

He points to the fact that the traditional political divide between left and right in Western countries is already being replaced by a separation between those ‘above and below the line’. “The people above the line can adapt to technological change, they can adapt to globalization. They see themselves as thriving in this world. Whereas the people below the line are the ones for whom technological advancement and globalization represent threats, not only economically but socially, in terms of their communities.”

The worry for Professor Snyder is that, as the impact of AI and automation grows, increasing numbers of people will drop below the line. Across the globe, there is already considerable rage at globalization, elitism and technology, and at the undermining of basic values and the sense of self, he says. In addition, in the US, and in many European countries, anxieties about immigration, and about the effect of technology on employment, are interacting in dangerous ways.

“I see support for the market economy, as a way to organize economic activity, going down,” he says. “I don’t know what’s going to replace it, or what the implications are. But support for market-oriented economies has to be grounded in the sense that they offer benefits to most people.”

The role of business schools

Having served as Dean at Kellogg and INSEAD, Professor Jain foresees the digital revolution having a significant impact on teaching in business schools. Courses that are well structured, such as some of those in accounting and economics, could be taken online by students prior to the official start of their program, he suggests. Then, when they arrive in class, their courses can be focused on topics such as critical thinking, which only humans are capable of teaching.

“What we as professors need to do is push the students to think of new ideas and new reasoning,” Professor Jain says. While programs will probably become shorter, they are also likely to contain more courses that rely on human interaction, such as those based on project work and fieldwork.

However, it will be the professors, rather than the students, who will face the greatest challenges in this type of future, he suggests. “Students today are demanding a different type of interaction than that which we’re used to – and for us change is more difficult. We have gotten used to a particular rhythm, a particular style of teaching. More training will be required for the faculty than the students.”

Professor Snyder, who has also held two other business school deanships (University of Chicago and University of Virginia), notes that the term ‘business school’ is already something of a misnomer. “We do teach the higher-value activity related to business, but ‘leadership’ and ‘management’ come to mind as more accurate descriptors.”

To date, he adds, management education has been based on the fact that humans both compete and collaborate. “Now we are seeing machines as both competitors and collaborators.”

However, the three professors agree on one thing, the fundamentals of what they teach is not going to be so different in the future.

“We will still teach them how to think,” Professor Jain explains. “We still teach them how to get the best out of the people they work with, as these sorts of interactions will become more and more important in the future. And we will still teach them how to put structure onto unstructured problems.”

Professor Rai concludes by highlighting possibly the greatest challenge that will be presented to him and his colleagues. “How do we build the capacity to adapt into our students?”